Setting up a “Just Transition Fund”. Frans Timmermans, Executive Vice President in charge of the European Green Deal, has repeatedly said these words as a mantra, seeking to reassure MEPs about the costs of the energy transition for coalfields in coal-mining areas during his hearing at the European Parliament on October 8 (1).

As for a reason: the end of coal seems inevitable. The new President of the European Commission, Ursula Von der Leyen, declared she wanted to make the European Union the “first carbon-neutral continent by 2050”. Coal is responsible for more than a quarter of Europe’s greenhouse gas emissions(2). The technology that would allow its use accompanied by the capture and storage of emitted CO2 is not considered on a large scale.

If such an ambition is not an option – the IPCC now expects a global warming rising up to 7°C more by 2100(3) – collateral economic and social damage to mining regions in the EU could be severe. COP 24 President Michal Kurtyka, Secretary of State to the Polish Minister of the Environment, made no mistake in pointing out the difficulties of overcoming fossil fuel dependency in the Silesia Declaration on Solidarity and Just Transition , signed by 48 heads of state. Indeed, ending the coal industry means cutting nearly 450,000 direct jobs across Europe . The bill will balloon as well: in Poland, for example, where coal still accounts for 84% of the national energy mix, the cost of the transition is estimated at 80 billion euros by 2030, and 115 to 160 billion euros by 2050 to “de-carbonize” the entire energy system and the industry sector.

Anticipating and taking into account all the consequences of such a change is a crucial issue for the European Union. Social acceptability and economic reconversion of coal-mining regions depend on it. What European strategy to adopt to make this energy transition just, so that it is not “just” a transition?

The abandonment of coal: A pan-European challenge

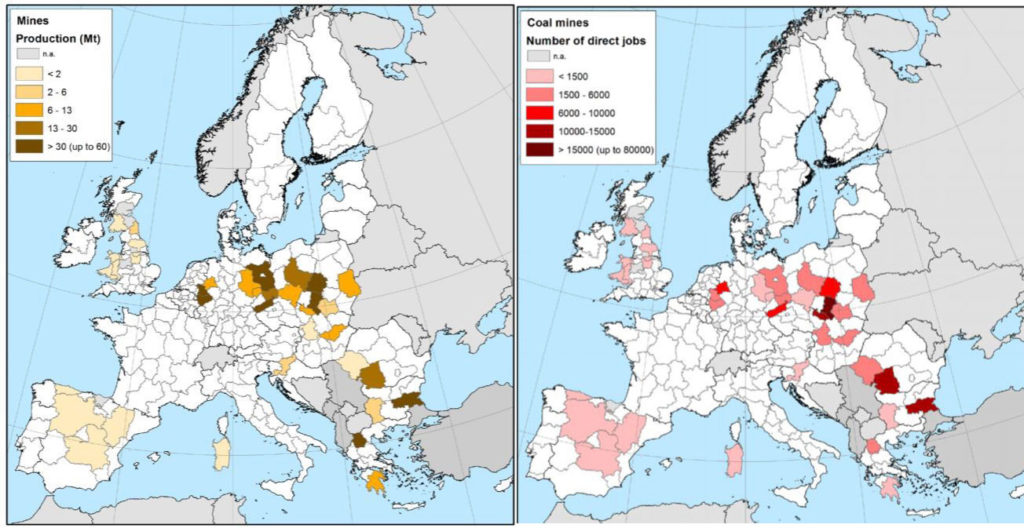

41 regions(7) in 12 Member States(8) still have active coal mines. Poland is the Member State with the largest number of coal mines (35), followed by Spain (26), Germany and Bulgaria (12 each)(9) . In terms of direct employment, Poland has 99,000 workers, Germany 25,000, Czech Republic 18,000, Romania 15,000 and Bulgaria 12,000(10). The abandonment of coal is therefore a pan-European challenge.

Left: Production of coal mines still in operation in the European Union (11)

Left: Production of coal mines still in operation in the European Union (11)

Right: Distribution of jobs in the European coal-mining regions(12)

In addition, the vast majority of coal-mining regions are already experiencing economic difficulties. Indeed, the unemployment rate is much higher than elsewhere. In the Silesian region of Poland, the youth unemployment rate is 39%(13). In Greece, in the region of Western Macedonia, which depends for the most part on mining, the overall unemployment rate is 29%(14). The low diversification of economic activities in the mining regions and the high average age of coal workers complicate the economic reconversion of these territories. In addition, the reluctance to close coal mines by some states and regional authorities can also be explained by their direct involvement in this sector. While they represent a source of revenue for the regions, the Polish government is the majority owner of the largest coal company and shareholder of the country’s second largest company(15).

A European strategy that is first and foremost preventive

In order to study the ways to avoid a sudden outflow of coal, the European Commission set up at the end of 2017 the Platform for Coal-Mining Regions in Transition(16) . Led by DG ENER (17), in collaboration with DG REGIO (18) and DG RTD(19) as well as with operational groups in the territories, the platform supports 13 pilot regions in seven Member States:

It aims to ensure multi-level governance between the various actors involved in the energy transition (European authorities, national authorities, regional authorities, trade unions, manufacturers, NGOs, etc.). The aim is to facilitate the development of long-term projects and strategies in coal-mining areas with a focus on social equity, energy and economic diversification and requalification. The platform offers the coal regions expertise on the use of European funds and how to attract more private investment. There is no question of being limited to compensatory measures for the employees once the mine is closed. If the energy transition in the coal regions could create around 900,000 jobs by 2030 (20) according to the European Commission, it is probably still too early to assess the effectiveness of the platform and its ability to influence policy makers.

The “Just European Energy Transition Fund”: an incentive-based approach?

However, the platform is not enough to convince the last three reluctant Member States to commit to carbon neutrality in 2050, namely Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic. Their agreement is however necessary to adopt the Climate Pact desired by the new Commission in the first 100 days of its mandate, in order to confirm this objective at European level. The creation of a new European fund to support the coal-mining regions in their transition may change the situation(21), but it is still somewhat unclear at the moment. Günther Oettinger, outgoing European Commissioner to the Budget, has indicated an amount ranging from 8 to 12 billion euros over seven years(22) . Polish Energy Minister Krzysztof Tchórzewski said Poland’s energy transition would require more than € 900 billion, including shutting down its coal plants while increasing its renewable energy capacity(23). However, the estimated 900 billion euros will not necessarily come from public funds: an attractive regulatory framework would make it possible to drain most of this amount in the form of private investment. For example, the Baltic Sea holds significant potential for offshore wind generation which would result in the creation of thousands of jobs(24) (assembly lines, port infrastructure, specialized vessels, etc.). In order to attract private investors to Poland, DG COMP(25) could ease tendering requirements in coal-dependent countries, while the European Investment Bank would abound some loans. At the same time, the Polish government should succeed in ensuring a stable regulatory framework and impartial justice to have the capacity to settle issues without political interference. Such sharing of tasks, which does not only concern Poland, would benefit from being negotiated in a peaceful atmosphere between the governments concerned and the European institutions. The balance to be struck between European solidarity and fair prices will undoubtedly be a delicate exercise for the new European executive.

Only one thing remains true: once a symbol of European cooperation more than fifty years ago, coal is now testing the unity of the 28 Member States to succeed, which may be the global challenge of the 21st century: to limit global warming to below 2 degrees.

CONFRONTATIONS EUROPE

CONFRONTATIONS EUROPE

Gabrielle Heyvaert,

Project Manager Energy with the collaboration of Michel Cruciani, pilot of the Energy group

- Hearing of Frans TIMMERMANS, Executive Vice-President-designate, European Green Deal, European Parliament

- International Energy Agency, CO2 Emissions from fuel combustion, 2018 (29 % in 2016)

- Up to + 7°C in 2100: French climate experts worsen their projections on global warming, Le Monde, September 17, 2019

- Silesia Declaration on Solidarity and Just Transition

- Alves Dias, P. et al., EU coal regions: opportunities and challenges ahead, EUR 29292 EN, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2018

- Polish Electricity Association (PKEE) report “The contribution of the Polish energy sector to the implementation of global climate policy”, December 2018.

- Regions” within the meaning of the European NUTS 2 nomenclature: “Basic regions for the application of regional policies”

- Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, United Kingdom

- Ibid.

- Polish Electricity Association (PKEE) report “The contribution of the Polish energy sector to the implementation of global climate policy”, December 2018.

- Alves Dias, P. et al., EU coal regions: opportunities and challenges ahead, EUR 29292 EN, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2018

- Ibid.

- Anja Bierwirth et al., “Phasing-out Coal, Reinventing European Regions – An Analysis of EU Structural Funding in four European Coal Regions”, Wuppertal and Berlin: Wuppertal Institute for Climate, Environment and Energy, 2017.

- Eurostat data

- Anja Bierwirth et al., “Phasing-out Coal, Reinventing European Regions – An Analysis of EU Structural Funding in four European Coal Regions”, Wuppertal and Berlin: Wuppertal Institute for Climate, Environment and Energy, 2017

- Page of the The platform for coal regions in transition, European Commission

- Directorate-General of Energy

- The Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy

- The Directorate-General for Research and Innovation

- Press release – European Commission, 11 December 2017

- Renewable energies: the EU wants to encourage the worst performers to do better, Les Echos, 26 July 2019

- Agence Europe, 10th october 2019

- Poland stirs dispute over cost and meaning of carbon neutrality, 4 October 2019

- Michel Cruciani, “The rise of offshore wind energy in the North Sea: a strategic challenge for Europe”, Etudes de l’Ifri, Ifri, July 2018

- The Directorate-General for Competition