The EU is one of the most efficient major economies in tackling greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and it is going to achieve its emission reduction target for 2020. EU GHG emissions were down in 2018 by 23% from the 1990 levels, while the target set already in 2007 was 20%. However, much more effort is needed in the EU and worldwide to be in line with the Paris Agreement target to limit global warming to 2°C, let alone to 1.5°C by the end of this century.

Prior to the 2015 climate conference in Paris, the EU introduced the target of reducing its GHG emissions by 40% by 2030 compared to the 1990 levels. Following the Paris Agreement this target needs to be revised upwards by the end of 2020, as well as its long-term target for 2050. Moreover, with the current insufficient commitments submitted by the Parties to the Paris Agreement, the EU needs to take climate action also at global level. The EU should further reinforce its capacity for climate diplomacy and strengthen its geopolitical relations by shaping accordingly its foreign policy, but also trade, development, aid, security and conflict prevention.

Since the Paris Agreement, several reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) have attracted substantial public attention as they underline the urgency to act now in order to combat climate change and prevent greater harm to humans and the ecosystem. In particular, the IPCC published in October 2018 its special report on the impacts of global warming by 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change. The report concludes unequivocally that continued action in line with current commitments is not compatible with pathways consistent with limiting warming to 1.5°C. If current commitments made by the Parties to the Paris Agreement were fully implemented, emissions in 2030 would roughly be twice the amount compatible with the long-term temperature goal of 1.5°C. However, the gap is even bigger as many countries have not adopted sufficient measures to reach their Paris commitments. The current state of implementation of policies and measures is likely to result in global warming by 3.2°C. The report underlines that we can already experience the consequences of global warming of 1°C and mentions a number of implications of climate change, which could be avoided by limiting global warming to 1.5°C rather than to 2°C.

Against the background of this overwhelming scientific evidence, the numerous occurring extreme events and the insufficient action by major emitting countries to combat climate change, the involvement of civil society has intensified over the last years. Most importantly, the protests initiated by Greta Thunberg in summer 2018 have induced the new movement of ‘Fridays for Future’ which has brought thousands of students to the streets every Friday for the last several months. One of the key demands of youth engaging in Fridays for Future is for politicians to listen to climate science and act accordingly.

After the publication of the IPCC report on the 1.5°C impacts and in view of the climate conference in Katowice, for the first time, the European Parliament (EP) called in its October 2018 resolution for an increase of the EU GHG emission reduction target of 55% by 2030. Moreover, the EP considered that the profound and most likely irreversible impacts of a 2°C rise in global temperatures might be avoided if the more ambitious Paris target of 1.5°C is pursued, but this would require rising global GHG emissions to fall to net zero by 2050 at the latest. For this purpose called also the Commission to propose an EU long-term mid-century net-zero GHG emission strategy. In its more recent resolution of March 2019 for climate neutral economy in accordance with the Paris Agreement, the EP reiterated its position that the EU needs to strive towards reaching net-zero GHG emissions as early as possible and by 2050 at the latest. Earlier in July 2018, the EP had adopted a report on EU climate diplomacy and emphasized the EU’s responsibility to lead on climate action as well as conflict prevention. The report stresses that EU diplomatic capacities should be strengthened in order to promote climate action globally, support the implementation of the Paris agreement and prevent climate change-related conflict. It thus covers major areas of EU climate diplomacy.

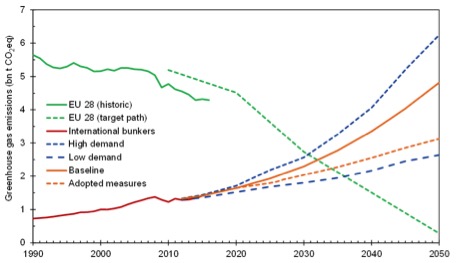

The EU in order to implement its commitments for GHG emission reductions by 2030 under the Paris Agreement put in place by May 2019 (end of the previous EP legislature term) numerous legislations relating to many different economic activities. However, as every bit of warming counts, the EU needs to reinforce its climate policies, in particular regarding the increasing emissions of aviation/maritime sectors, as well as, of the non-CO2 GHG emissions (e.g. methane, sulphur hexafluoride – SF6, etc.) which drive more than 30% of today’s global warming. In particular, emissions from international civil aviation and maritime transport are two of the fastest growing GHG emission sources; however, their emissions are left out from the Paris Agreement. Two specialised UN agencies for these sectors – the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) and the International Maritime Organization (IMO) were mandated to address these emissions, but their long-waited emission reduction measures are still under consideration. Despite efficiency gains due to technological and operational improvements, emissions from international aviation and maritime transport have grown at an annual average of 4.0% and 2.6%, respectively. If the world pursued an emission path that is compatible with the Paris Agreement while international aviation and shipping remain unchecked, the two sectors would be responsible overall for 20 % to 50 % of global CO2 emissions in 2050, according to an EP 2015 report.

Challenges arise from the plans released by the Commission president-elect, such as a new European Green Deal in her first 100 days in office for new EU climate-neutrality commitment for 2050 and an increased EU 2030 emission reduction target to at least 50%. Subject to the level of ambition of other major emitters by 2021, the EU should put forward a comprehensive plan to increase the EU’s target for 2030 towards 55%. At the European Council in June 2019, the EU Member States (MSs) failed to adopt a 2050 carbon neutrality target for the EU, although some MSs have already adopted climate neutrality targets. The current EU Finnish Presidency is likely to renew efforts to adopt the 2050 carbon neutrality target in the Council. Anyhow, if the EU is to respect its commitments under the Paris Agreement and to lead by example in the fight against climate change, it needs to take some bold decisions by the end of 2020 at the latest.

Dr Georgios AMANATIDIS

Research administrator, Policy Department for Economic, Scientific and Quality of Life Policies, European Parliament

* The opinions expressed in this document are the sole responsibility of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position of the European Parliament.